STEMM the flow: More work needed to support women in medical research

Jessica Borger

Federal government investment in the National and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) has remained unchanged in recent years, which, together with newly-revised funding schemes, have resulted in a reduction in the number of successfully-funded research projects.

The funding uncertainty across Australia’s medical researchers has serious consequences for those most impacted by inequity, including early- and mid-career researchers (EMCRs), and women.

In response to the recent release of the outcomes of one of these schemes, the Investigator Grants, we analysed if enough has been done to help support and retain women in medical research.

Aim to reduce researchers’ dropout rate

The Investigator Grants, NHMRC’s largest funding scheme, was developed as part of a major reform of NHMRC’s grant program to address concerns that the high volume of applications for funding was having negative effects on Australian health and medical research , particularly the attrition of EMCRs.

Through combining the investigator’s salary and research expenses for five years, and capping at two the number of submitted or held grants for those who didn’t obtain an Investigator Grant, the NHMRC hoped this would enable researchers to focus on conducting and publishing research.

In the conceptualisation of the new grant program, the NHMRC was guided by a number of principles, including equity, to provide opportunities for talented researchers at all career stages, and sought to minimise both disadvantage and selective advantage, but it failed to specifically identify equity measures in respect to supporting the retention of women.

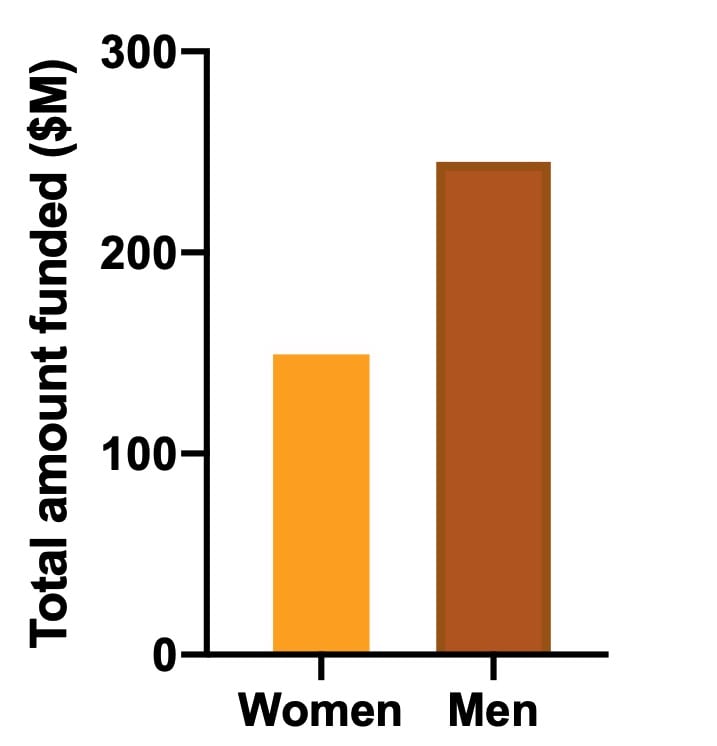

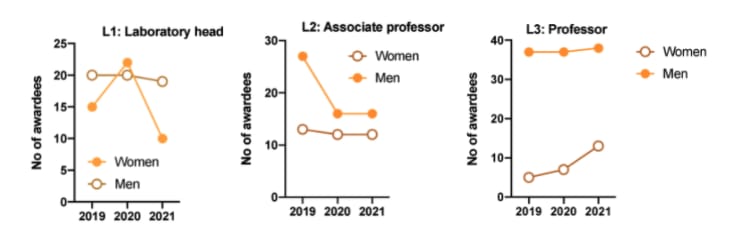

The 2021 outcome (Figure 1) identifies that sustained gender bias and an unremitting loss of women from STEMM continues due to a disproportionate allocation of funds.

Our statistical analysis of the funding outcomes of the first three years of this new Investigator Grant scheme has revealed that men have received significantly more ($95.1 million) than women per year. Further, this starts from the L1 independent laboratory head stage, and exponentially falls with increased seniority.

Gender disparity in medical research

Women are poorly represented in the STEMM workforce. There’s been no significant change in the “scissor graph” demographic for decades, which clearly quantifies that women in STEMM tend to be highly biased towards ECRs due to a dramatic gender loss as researchers independently establish their laboratories.

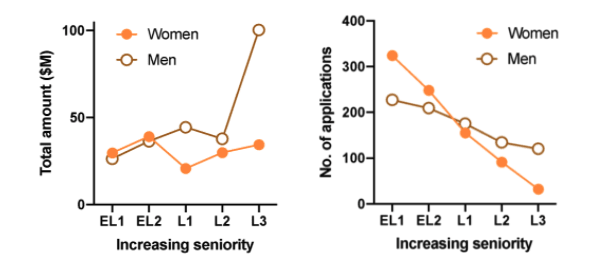

Strikingly, the 2021 Investigator Grant outcomes reflect a similar scissor graph demographic in respect to funding of women medical researchers.

Figure 2 clearly identifies a reduction in the number of women applicants as seniority of the leadership level increases. While more women applied at the EL1 and EL2 early career stages compared to men, approximately two-fold fewer women applied at L2 (associate professor), and four-fold at L3 (professor), averaged across all three years.

The lack of retention of women researchers in academia is attributed to numerous engendered factors, including reduced career opportunities, the burden of low promotability tasks, and disparity in the distribution of domestic unpaid workloads (64% compared to 36% men).

It’s now obvious that the well-documented effects of the gendered bias in peer review is also a significant and ongoing contributing factor to the continual attrition of senior women from medical research, and that strong action is required to prevent its continuation.

NHMRC hasn’t improved gender bias

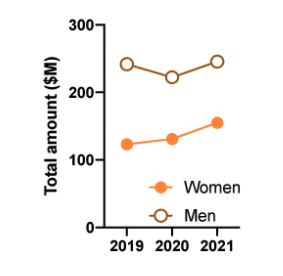

Since the implementation of the Investigator Grants, our analyses identify that men are consistently awarded at least 20% more funding than women, equating to $300 million in the first three years of the scheme (Figure 3).

A positive trend, which requires significant acceleration in coming years, is that in 2019 men received 32% more funding than women, and this gap has gradually reduced to 23% in 2021.

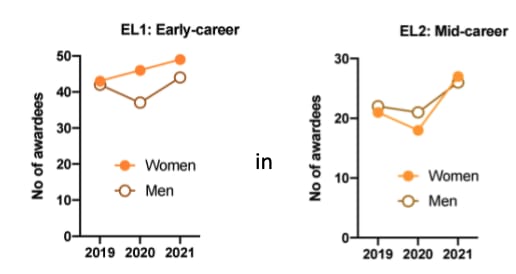

However, this hasn’t improved retention of women at the independent laboratory head stages, because the funding gap has been filled by an increased number of successful women ECR applicants. As a result, the “scissor graph” will not change.

At the early career levels (EL1 and EL2), there’s equitable distribution of Investigator Grants funding (Figure 4).

Yet for these successful early career researchers, the quantified gender bias of the funding, which increases with level of seniority in terms of a decline in the number of applicants and funding levels (Figure 5), is disconcerting for women striving for a long-term research career in academia.

Indeed, at the most senior level (L3), more than three times the number of men are funded than women.

Mitigating the attrition

To mediate the fallout of the failure of NHMRC Investigator Grants to equitably support women, significant action is immediately required.

Priority funding urgently needs to be considered for EMCRS to support the establishment of their careers, and the retention of senior level women scientists to close the gap and maintain a diverse generation of leaders and mentors for future researchers.

Read more: Women in science: Putting gender imbalance under the microscope

The NHMRC, other funding bodies, universities and medical research institutes need to actively work towards attaining equal quotas and funding across gender and career stages. These approaches would deliver the most equitable roadmap to support our next generation of biomedical researchers, and ensure retention of women in STEMM into the future.

This article was authored by Jessica Borger and co-authored with Professor Louise Purton, head of the Stem Cell Regulation Unit at St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research.

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article